Calculating Excess Deaths – Problems with the

New U.K. Methodology

Below are some concerns about the latest U.K. modelling of “excess deaths”. The general point I am making is that the new method seems to be answering a question (forecasting current year-over-year changes in unexpected deaths) that is peripheral to the research question that everyone is asking:

Why are excess deaths so high:

-

now in the post-Covid period (much of 2022, 2023, 2024),

-

compared to what they were during the main Covid (2020,2021, some of 2022)

-

and before Covid (say 2015-2019))?

A quick note about me, the analyst who wrote this critique: I worked for about 40 years as a statistician/data scientist, splitting my time between the Ontario provincial government in Canada and a large western Canadian research university. That time included using and developing population projection methods, building regression models, and developing specialized mathematical modelling techniques. Not to mention, plenty of descriptive reporting.

Naturally, these are my opinions and don't represent the views of past or present employers. In a follow-up blog, I will use the numbers provided by ONS to estimate the changes in death rates during these periods, and compare the latter periods to the former.

Problems with the new Model

The bolded comments are from the document Estimating excess deaths in the UK, methodology changes: February 2024 (Office of National Statistics, United Kingdom). In a few places, I have added underscores for emphasis. My comments follow in non-bold type.

-

“This statistical model provides the expected number of deaths registered in the current period, if trends in mortality rates remained with the same as those from recent periods and in the absence of extraordinary events affecting mortality, such as the peak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.”

-

This is not the question in most people’s minds. With this model, a portion of the rise in deaths due to Covid, Covid lock-downs and Covid vaccines becomes “baked in the cake” and this are no longer considered excess deaths. They are the new normal. Thus, the effects of Covid, Covid lock-downs and Covid vaccines on the death counts is attenuated by the method and partially obscured.

-

-

“Each model is fitted to five years of data with a lag of one year from the end of the fitting period to the current period, so the expected number deaths in each week or month has its own five-year baseline period. For example, when estimating the expected number of deaths in January 2024, the model will be fitted to data spanning February 2018 to January 2023.”

-

Problem: With this method, increased deaths in 2023 (for example) are diminished in importance. Deaths in the years 2018 to 2023 are now normalized, so that excess deaths in 2023 are reduced, since the new calculation “expects” them, based on the deaths in the previous 5 years, which were high by historical standards.

-

So, this method answers a research question that is not the research question that interests most people (i.e. how does the number of deaths in 2023 compare with the number of deaths during the pre-pandemic period, This gives an (admittedly rought) indication of the effects of the pandemic, pandemic lock-downs and pandemic vaccinations. The new method might be useful for forecasting excess deaths, from one year to the next, but that’s not the main thing that interests most people.

-

-

“When using a quasi-Poisson regression model, modelling the number of deaths as the dependent variable, and including the natural logarithm of population size as an offset term is analogous to modelling the mortality rate in each age-sex-geography stratum.”

-

As noted above, this modelling may be useful for current year planning purposes, but it doesn’t address the main issue, which is how did the death counts differ from pre-pandemic years, to pandemic years, to post-pandemic years. For most people, that is the main concern. The method tends to reduce the “excess deaths” count, which raises suspicions. i.e. is that the real intent of the new methodology?

-

It is akin to a population projection model, which is a valid tool, but does not lead to understanding of the dynamics driving the process (in this case, long-Covid, Covid lock-down side effects and Covid vaccine adverse efficts).

-

-

“In our current approach to estimating excess deaths in England and Wales, and that of the devolved administrations of Scotland and Northern Ireland, the expected (baseline) number of deaths is estimated as the average number of deaths registered in a recent five-year period. In contrast, our new methodology is based on age-specific mortality rates rather than death counts, so trends in population size and age structure are accounted for. Furthermore, the five-year average mortality rate is adjusted for a trend, so historical changes in population mortality rates are also accounted for.”

-

The use of a “time-trend” variable such as this one, seems to ‘hand-wave’ away and obscure the point in question, which is precisely the “historical changes in population mortality rates”. What are the trends and what is causing them?

-

-

“The new and current methods produce estimates of excess deaths with similar trends and seasonal patterns over the nine-year period before the coronavirus pandemic, 2011 to 2019 (Figure 1). From 2011 to 2013, estimates from the new method are generally higher than those from the current method. However, estimates from the new method are consistently lower than those from the current method from 2015 onwards, particularly in 2019.”

-

People will naturally be suspicious of a new methodology that results in more unexpected deaths in the pre-pandemic period and fewer unexpected deaths in the pandemic and post-pandemic periods. This will lead to speculations that the government is trying to diminish concerns and therefore partially absolve itself of responsibility for increased excess deaths in the latter periods (which are the periods that people actually care about).

-

-

“The new and current methods estimate similar numbers of excess deaths during the pandemic (Figure 2). In particular, the two approaches produce similar peaks in estimated excess mortality in the second quarter of 2020 and the winter of 2020 to 2021. However, estimates from the new method are generally lower than those from the current method throughout the latest year, 2023, by an increasing amount.”

“On an annual basis, the new method estimates 76,412 excess deaths in the UK in 2020, compared with 84,064 estimated by the current method (Table 2). For context, the highest number of excess deaths estimated by the new method over the nine years before the pandemic is 30,858 in 2015. In the latest year, 2023, the new method estimates 10,994 excess deaths in the UK, 20,448 fewer than the current method.”

-

What else can one say, other than “this seems rather convenient” (from the government's point of view, anyway).

-

“These increasing trends in population size and ageing, and the generally decreasing trend in mortality rates, are not accounted for by the current methodology for estimating excess deaths. However, they are reflected in the new methodology.”

-

This issue strikes one as something of a red herring, in terms of the question of excess deaths in the 2020 and beyond period compared to the five years before that. Though population growth and population aging generally will lead to more deaths, over these time-scales the effect would not be all that large. Furthermore, the population growth was almost exclusively due to migration, which is heavily concentrated in younger age groups, which won’t be expected to experience many deaths, relatively speaking.

-

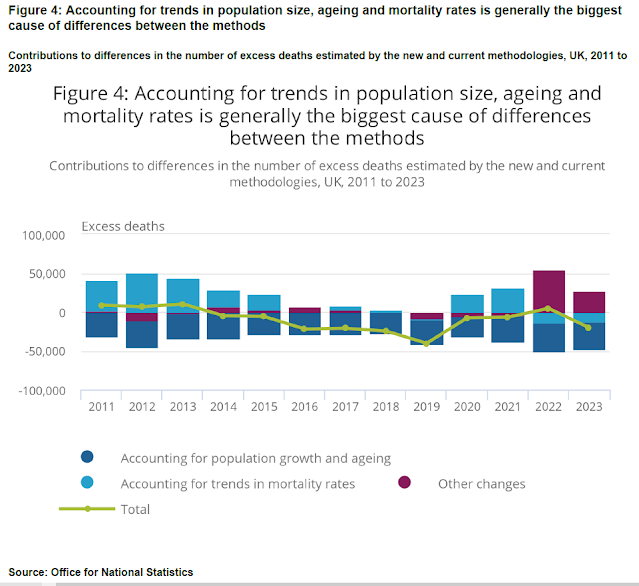

A Note on the Graph

The graph below is from the Office of National Statistics methodology document.

Note that in 2022 and 2023 the biggest cause of differences between the two models is simply given as “Other changes”. This is vague – a description like “Other changes” can hide a lot. After all, the “Other Changes” are precisely what most people are wondering about.

What are these "Other changes"?

-

Long term effects of Covid itself?

-

Long term effects of Covid measures such as lock-downs?

-

Long term effects of Covid vaccines?

The new model seems to be better at obscuring than revealing. Good sciences should be the other way around.

No comments:

Post a Comment