I will be heading out on a road trip – with a bit of luck,

that will include observing a spectacular total eclipse in the beautiful state

of Oregon, U.S.A.. If all goes well, I

will blog about that later.

That will take some time away from blogging, so I am

presenting a piece that I wrote quite some time ago (late 1990’s), concerning

my attempt to “beat the horse races”, with the applications of computing power,

data analysis, intelligence and dogged determination. I did ok for few years, and learned a lot of

statistical techniques (via concurrent courses in multivariate analysis). I certainly learned plenty about the pluses

and minuses of data mining, and the wisdom behind the notion that one should be

careful about post-hoc analyses.

Plus, I had some fun – there is nothing quite like a big

score on a long odds horse that your system predicted, that hardly anybody thought

had a chance.

And some of the photos are old, so the quality isn't great, but they are authentic, so there's that. The better photos are from google images.

Horse racing Days (2)

II – The World of the Racetrack

Superstition and Conspiracy

Gambling is a strange thing.

Even the most rationally trained mind can be awash in superstition while

in the throes of gambling fever. I was

studying mathematics at university at this time, so I should have had some

protection from the various fancies and fallacies that gamblers are prey

to. I can only imagine what the

mathematically naïve must go through.

I can recall wandering around the racetrack, searching for

the ‘spot’ before the race. I felt,

irrationally, that there was a zone of luck, that if located, would lead to

success. It moved around the real estate

of the racetrack, sometimes appearing in the grandstand, other times at the

finishing line, often in obscure nooks and crannies of the building. Other places were absolute dead zones, the

habitats of zombies and broken men. Bars

at the track were especially bad for this, and in general, drinking was the

kiss of death. If nothing else, this

belief managed to get me a lot of exercise, and kept my alcohol consumption to

a minimum.

Of course, one still attempted to handicap the races,

applying logical principles of prediction to the problem at hand. These included past performances, early speed

vs. closing speed, jockey and trainer records, blood lines, claiming prices,

post bias, weather, and myriad other factors.

But the problem was an immense one, so it was difficult not to lapse

into superstition at any given time.

Another favorite delusion was the coincidence of names. One would see a horse with a name that had

personal associations, and be tempted to see a deep meaning in it. Perhaps it was the name of a woman that one

was romantically interested in. Other

times it might be a word or phrase that had a peculiar resonance, for instance

“Pain”. The worst was when your own name

appeared in the horse’s name. These were

exceedingly difficult to pass up, regardless of the objective facts of the

horse. The knowledge that your racing

mates would look pitifully upon you, if such a horse came in when you had not

bet on it, was enough to ensure that you would put at least a couple of bucks

on it. With a name like Dale, I had to

face this situation surprisingly frequently.

What might be called the numerological fallacy was always

popular. This is the desire to see deep

patterns in a run of numbers, familiar from roulette or dice games. This might present itself in a simple form,

such as the observation that horses numbered six had been winning a

disproportionate share of races, therefore one should start betting six. Conversely, it might be noted that the four

horse had not won all day, so it was ‘due’.

In its more advanced form, numbers that were multiples of each other

might be favored, or consecutive runs, like a straight in poker. I once suggested, at least half

facetiously, to some fellow bettors that

the day’s races had been easy to pick, as all of the winners had been prime

numbers. They took me quite seriously.

As desperation set in, truly bizarre appeals to the forces

of luck might be attempted. One person

of my acquaintance would sometimes poke a pin through the first page of the

Daily Racing Form, then bet every horse whose past performances happened to

fall on the pinhole in the underlying pages.

Others might read significance into where some beer spilled on the

Racing Form, or what street numbers they happened to notice on the way to the

track.

Then there were the standard beliefs of the racetrack, some

purely superstition, and some, like old wives’ tales, an amalgam of folklore,

fact, and fancy. Never bet against a

grey. Female jockeys are bad luck. A filly can’t beat a colt. Blinders mean a horse is wild. A horse will never win its first time

out. A jockey can’t win two in a

row. Outside speed can’t win a sprint,

and inside speed can’t win a route.

And then there were always dark hints of conspiracy, rigged

races, and what we referred to as ‘shafts’.

After a time, it is natural for gamblers to think along these lines. My brother Jim always maintained that this

was the counsel of fools, that if you didn’t believe in the fundamental

integrity of the game you were doomed to lose.

Another of my brothers, Craig, was a fatalist, who believed that the

entire cast of characters involved in racing were cheats. Every race was fixed, every jockey crooked,

every trainer a thief. He also claimed

that each racing card was carefully orchestrated, along the lines of a

wrestling card. A few favorites would be

let in, to set up the crowd for an unlikely longshot, that only the insiders

would be privy to. Alternatively, a

series of longshots would be allowed to win, to rattle the crowd, so that a

favorite in a later race would be allowed to go off at higher odds than it

should. Naturally, only the insiders

would be savvy to this fact, allowing them a big score on a racing coup.

I believe that a large part of the fascination with

gambling, and racing in particular, is tied up with these beliefs. There is something liberating about tossing

in one’s lot with blind luck. A winning

streak makes one feel transcendent, as if the powers of the universe are yours

to command. A bad losing streak has its

own perverse attraction, making one feel that he has been singled out by the

gods, like Oedipus, for special pain and punishment, for sins he may be unaware

of, but he has certainly committed.

The conspiracy theories have their allure, too. They give an extra intellectual dimension to

the game, with one always attempting to second guess the inside money. As with all conspiracy theories, elaborate

conspiracies within conspiracies could be projected. They, the powerful inside forces, may have

wanted us to catch the fix in the eighth race, so that we would bet the likely

fix in the ninth. Then, they would let

the ninth race come in true, which would, of course, not be true at all. Before long, the conversation would resemble

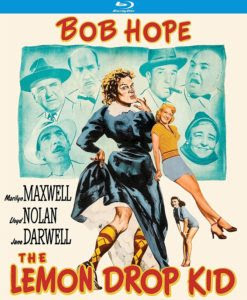

dialogue from the X-Files – or better yet, a Damon Runyon story like The Lemon Drop Kid.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Real life is pretty interesting, at the track, but fiction

can be almost as good. So, here’s a

short story that I wrote in those early years, about a horse-player and the

devil (probably).

A Dark Horse

Just

what might a gambler give up, to go on the winning streak of his life? Even he

can't know for sure. Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus legend is given a

Damon Runyon spin, in this short story.

For those who aren’t familiar with it, the Faustus legend is about

someone who sells his soul to you know who, for fame and fortune. Things are not nearly so simple for the character

in the story, though.

This

is a short story of about 6500 words, or about 35 to 45 minutes reading time,

for typical readers.

Amazon U.S.: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01M9BS3Y5

Amazon U.K: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B01M9BS3Y5

Amazon Canada: https://www.amazon.ca/dp/B01M9BS3Y5

Amazon Germany: https://www.amazon.de/dp/B01M9BS3Y5

Amazon Australia: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/B01M9BS3Y5

Amazon India: https://www.amazon.in/dp/B00OX60XJU

No comments:

Post a Comment